1000 YEARS OF JOYS AND SORROWS: A Memoir by Ai Weiwei. Translated by Alan H. Barr (2021)

Ai Weiwei is a well-known Chinese artist. His father, Ai Qing, was a well-known Chinese poet. Between them, their lives cover a century of Chinese cultural history.

Ai Weiwei is a well-known Chinese artist. His father, Ai Qing, was a well-known Chinese poet. Between them, their lives cover a century of Chinese cultural history.

Both wanted to explore the wider world outside China. Both believed that art and poetry were for the masses and not just the elite. Both believed in artistic freedom. Both were imprisoned by the Chinese government for exercising that freedom.

The first half of the book is Ai Weiwei’s biography of his father. Ai Qing was a loyal Chinese Communist who nevertheless believed writers could serve the Revolution best if they were true to their own vision. The regime disagreed.

The second half is Ai Weiwei’s own story. Unlike his dad, who was loyal to a cause, he was a rebel who confronted and rejected all forms of authority – governmental, cultural and traditional. The video above, a trailer for a 2012 documentary, gives an idea of his defiant spirit.

“Art should be a nail in the eye, a spike in the flesh, gravel in the shoe,” Weiwei wrote. “The reason art cannot be ignored is that it destabilizes what seems settled and secure.”

My interest in the book was awakened by learning it is one of Edward Snowden’s favorites.

The title of the book is based on verses from one of Ai Qing’s poems:

Of a thousand years of joys and sorrows,

Not a trace can be found.

You who are living, live the best life you can.

Don’t count on the earth to preserve memory.

Ai Qing was born in 1910, one year before the overthrow of the Manchu dynasty. He loved poetry and art and persuaded his father to give him money to go to France for study in 1929.

Ai Qing 1929

He lived in Paris among poor Chinese expatriates for three years, where he learned to speak French and love Russian literature. He later said these were the happiest years of his life. He returned three years later, having learned no marketable skills that would enable him to pay back his father.

When he got back, he moved to Shanghai, joined the Union of Left Wing Artists and was arrested just a few months later. He wrote his first poems during his three years in prison.

For years after that, he lived hand-to-mouth, subsisting on low-paid teaching jobs or the charity of his father. He managed to keep writing and was able to get some of his works published.

He was one of these poets who are inspired and driven to write, no matter what their circumstances. The themes of his poetry were the suffering of the Chinese common people as a result of exploitation and war.

He was married, divorced and had relationships with various women. He begat children who died in childbirth and infancy, probably as a result of poverty. He somehow managed to get his poetry published.

In 1941, he made his way to Yunan and joined Mao Zedong. Mao’s idea of the role of writers was that they were the propaganda arm of the revolutionary army and should be subject to military discipline.

Ai Qing argued about this with Mao to his face. He believed that writers could best serve the revolution by following their own inspiration.

He also said that Russians are more realistic in terms of their strategy and goals.

He also said that Russians are more realistic in terms of their strategy and goals. Everybody knows that corporations influence and manipulate governments behind the scenes. In Silent Coup, two British journalists show ways in which corporations are actually replacing governments.

Everybody knows that corporations influence and manipulate governments behind the scenes. In Silent Coup, two British journalists show ways in which corporations are actually replacing governments. Her first example is the ongoing struggle to keep Asian Carp, an invasive species, from jumping from the Mississippi Valley watershed to the Great Lakes Basin.

Her first example is the ongoing struggle to keep Asian Carp, an invasive species, from jumping from the Mississippi Valley watershed to the Great Lakes Basin. I worry about liberal over-reach — the attempt to make every claim on society a matter of rights.

I worry about liberal over-reach — the attempt to make every claim on society a matter of rights.  However, a couple of weeks ago, I picked up a nice, readable detective novel, without any wider social significance, from a free book exchange. Once I started reading, I found it hard to put down.

However, a couple of weeks ago, I picked up a nice, readable detective novel, without any wider social significance, from a free book exchange. Once I started reading, I found it hard to put down. In The Outline of Sanity, he wrote about an economic philosophy called Distributism, which never caught on, but dealt with issues that are still current today—business monopoly, increasing economic inequality and standardized mass production.

In The Outline of Sanity, he wrote about an economic philosophy called Distributism, which never caught on, but dealt with issues that are still current today—business monopoly, increasing economic inequality and standardized mass production.  He is a member of an old Palestinian family, with roots going back into the Ottoman Empire, and his history is, in part, a history of his own family. I emphasize the personal history in this post, although he himself mentions it only in passing.

He is a member of an old Palestinian family, with roots going back into the Ottoman Empire, and his history is, in part, a history of his own family. I emphasize the personal history in this post, although he himself mentions it only in passing.  We’re now living in Jack Welch’s USA, a nation of industrial decline, increasing poverty, increasing inequality and dysfunctional institutions.

We’re now living in Jack Welch’s USA, a nation of industrial decline, increasing poverty, increasing inequality and dysfunctional institutions. The founder and first president of Judenstaat is one Leopold Stein, a representative of the Socialist Labor Bund, a real-life revolutionary Jewish organization founded in 1897 and primarily based in Poland, Lithuania and Russia.

The founder and first president of Judenstaat is one Leopold Stein, a representative of the Socialist Labor Bund, a real-life revolutionary Jewish organization founded in 1897 and primarily based in Poland, Lithuania and Russia. Stark’s opponents, like Long’s, were themselves ruthless and corrupt, but Stark did not complain of unfairness. Instead he beat them at their own game.

Stark’s opponents, like Long’s, were themselves ruthless and corrupt, but Stark did not complain of unfairness. Instead he beat them at their own game.

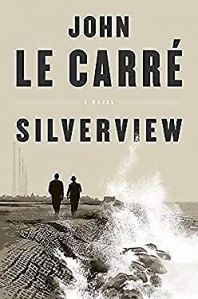

The Little Drummer Girl (1983), The Night Manager (1993) and The Tailor of Panama (2001) are about innocent people getting caught up in the machinery of international intrigue. The title character in A Perfect Spy (1986) is perfect because he has no loyalties.

The Little Drummer Girl (1983), The Night Manager (1993) and The Tailor of Panama (2001) are about innocent people getting caught up in the machinery of international intrigue. The title character in A Perfect Spy (1986) is perfect because he has no loyalties. Andrew Fowler, an Australian journalist, wrote about Assange at the height of his fame and success. He provides Assange’s back story and insights into his sometimes difficult character.

Andrew Fowler, an Australian journalist, wrote about Assange at the height of his fame and success. He provides Assange’s back story and insights into his sometimes difficult character. Stefania Maurizi, an Italian journalist who worked closely with Assange, took up the story where Fowler left off.

Stefania Maurizi, an Italian journalist who worked closely with Assange, took up the story where Fowler left off.

The village is sheltered by a magic tree, which was fertilized by fine wine and offers protection from the ravages of time. It is inhabited by an immortal witch named Brunilda. She will give you anything you ask, for a price, but her clients find that what they asked for was not what they wanted, and the price was harder to pay than they figured on.

The village is sheltered by a magic tree, which was fertilized by fine wine and offers protection from the ravages of time. It is inhabited by an immortal witch named Brunilda. She will give you anything you ask, for a price, but her clients find that what they asked for was not what they wanted, and the price was harder to pay than they figured on.

In this 2018 book, he argues that debt write-downs actually were economic policy in the ancient Near East, and are supported by the Hebrew Bible and the teachings of Jesus.

In this 2018 book, he argues that debt write-downs actually were economic policy in the ancient Near East, and are supported by the Hebrew Bible and the teachings of Jesus.

Austerity contributes as much to economic health as bleeding to biological health. That is to say, austerity has, so far as I know, an unbroken record of failure in promoting economic recovery. So why hasn’t the economics profession abandoned austerity, as the medical profession abandoned bleeding?

Austerity contributes as much to economic health as bleeding to biological health. That is to say, austerity has, so far as I know, an unbroken record of failure in promoting economic recovery. So why hasn’t the economics profession abandoned austerity, as the medical profession abandoned bleeding? Mills analyzed three power elites – corporate, military and governmental. He showed how they were largely independent of public accountability and public control, and were unrepresentative of the public at large.

Mills analyzed three power elites – corporate, military and governmental. He showed how they were largely independent of public accountability and public control, and were unrepresentative of the public at large. He concluded that members of these elites were not representative of the American people in their social origins, they had goals and incentives that didn’t coincide with the interests of the American people, and they were not accountable to the American people.

He concluded that members of these elites were not representative of the American people in their social origins, they had goals and incentives that didn’t coincide with the interests of the American people, and they were not accountable to the American people. Both the circus scenes and the nursing home scenes have a you-are-there quality that shows extensive research and also deep understanding of circus history, the Great Depression and the male psyche.

Both the circus scenes and the nursing home scenes have a you-are-there quality that shows extensive research and also deep understanding of circus history, the Great Depression and the male psyche.  We meet the protagonist, Lauren Oya Olamina, in 2024 at the age of 15 through a journal she keeps. She has already decided to found a new religion, called Earthseed. It would be based on the idea that “God is Change,” but that it is possible to shape God. Its long-range goal would to spread human life throughout the universe. All the chapter epigraphs are based on excerpts from its sacred book.

We meet the protagonist, Lauren Oya Olamina, in 2024 at the age of 15 through a journal she keeps. She has already decided to found a new religion, called Earthseed. It would be based on the idea that “God is Change,” but that it is possible to shape God. Its long-range goal would to spread human life throughout the universe. All the chapter epigraphs are based on excerpts from its sacred book.